From Catholic schools to public districts, administrators agree pandemic education is an individual effort

Originally published on the thesunchronicle.com

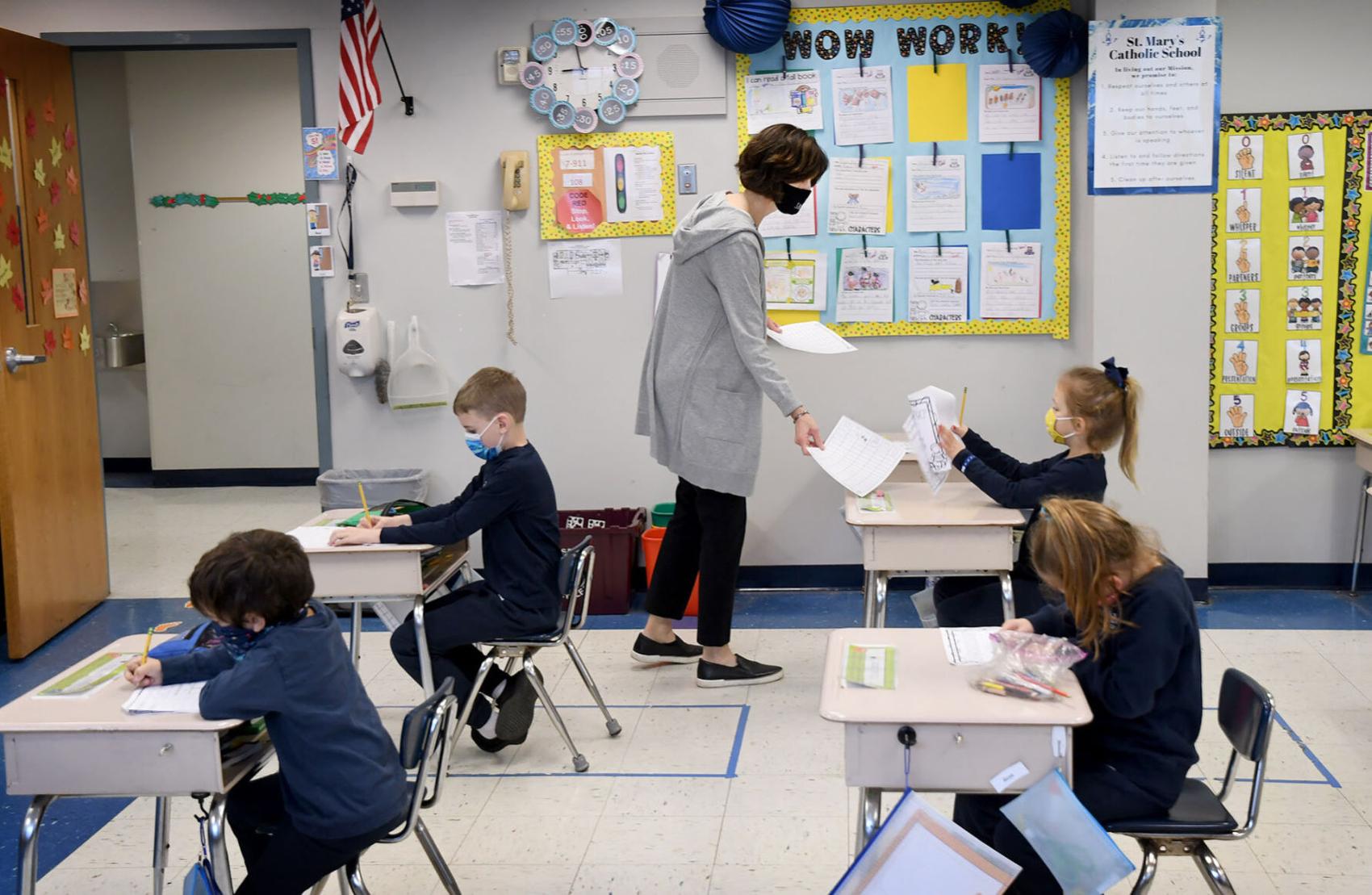

Julie McCarthy, a first grade teacher at St. Mary’s Catholic School in Mansfield, collects papers after a lesson.

For Tim Sullivan, the first true test of pandemic education came in October when the first Bishop Feehan High School student tested positive for coronavirus.

Until then, Sullivan felt like he was holding his breath, waiting to see how the protocols his staff spent months laying out would play out when put into action.

It was a Monday afternoon when the nurse got the call.

And while the plan was put in place — communicate, clean, contact trace — Sullivan, the president of the Catholic school in Attleboro, said he was weighed down in worry.

He worried about the individual student’s health. He worried whether the next five days would uncover evidence of the virus spreading throughout the school.

And he worried about how students, staff and parents would react. deneme bonusu

“How is this going to reverberate in the community?” Sullivan said he thought at the time. “It wasn’t until days later when people weren’t running off, when they came back to school and things moved on, that I felt relieved. After 24 hours it was like — OK, the community is ready to try this. We’re not ready to give up yet.”

The virus didn’t spread through the school. The student pulled through OK.

And since then, only two other members of the Bishop Feehan community have tested positive for coronavirus. Neither case was traced back to the school.

In several pitches last month encouraging public schools to reopen fully in-person this January, Gov. Charlie Baker has pointed to parochial schools as evidence that coronavirus is not spreading through schools like many feared it would.

“The data is pretty clear on this,” Baker said in early November. “Kids in school are not where the vast majority of community transmission takes place and the best example of all of that is probably the parochial school system, which has had almost 30,000 kids and 4,000 staff in-person since the middle of August and has less than 40 cases, none of which originated inside the school.”

Many families in support of a full reopen have taken that statement as further evidence to fight for a similar outcome in their own districts.

In updated guidance at the start of last month, state officials said schools should prioritize in-person learning even if a community is designated as “high risk” for spreading the virus.

Baker said keeping students remote carries mental health risks and learning loss that can have “real consequences.”

But not all Catholic schools are operating as normal.

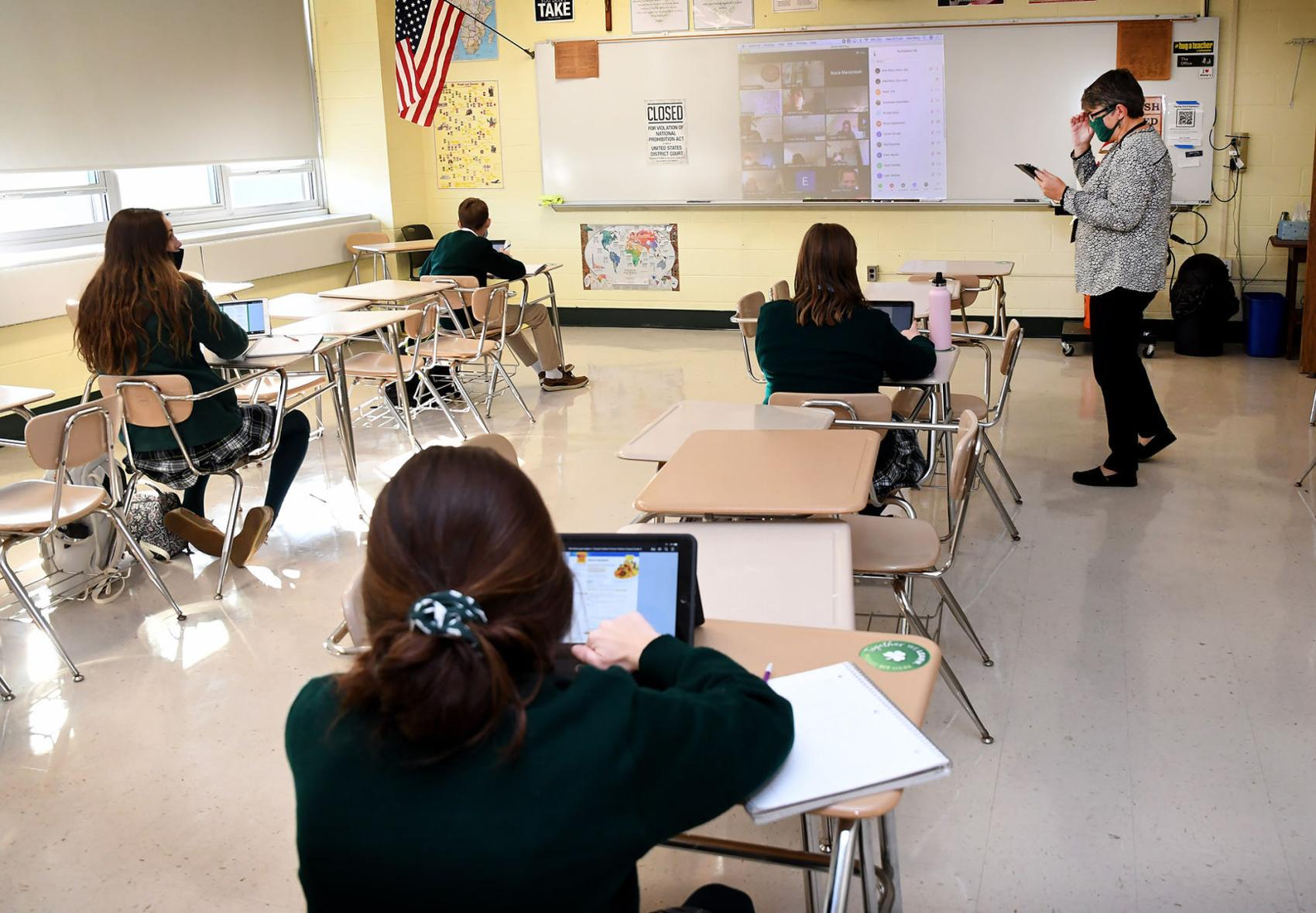

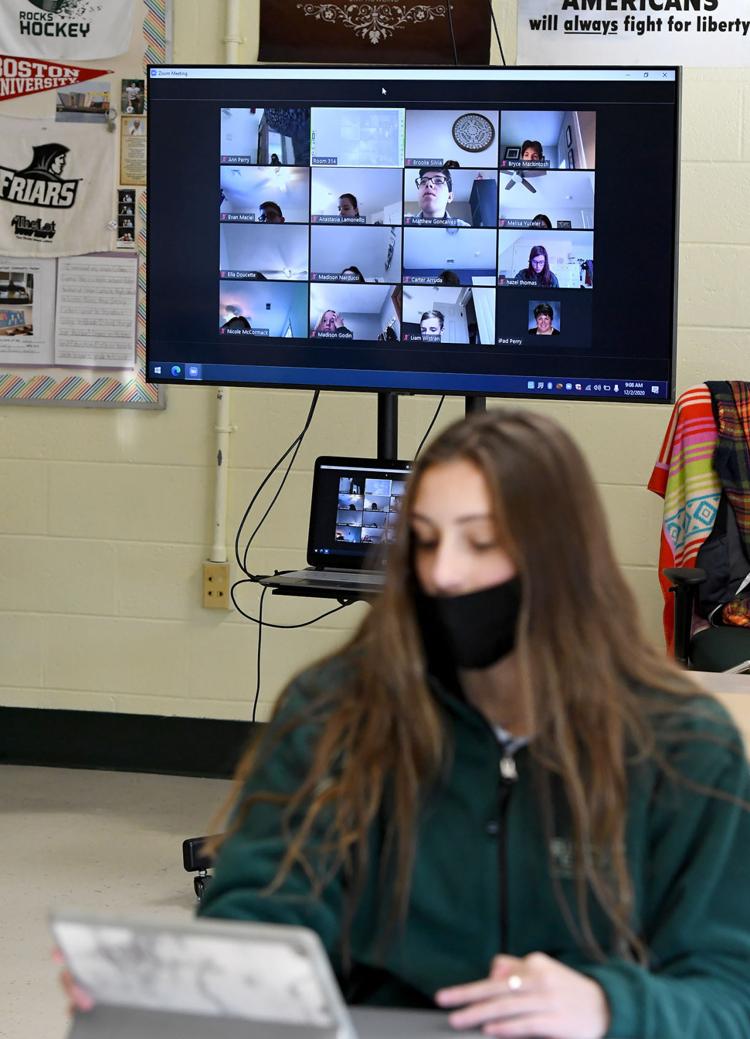

Bishop Feehan High School teacher Ann Perry conducts a freshman algebra class for both in-person and at-home students via Zoom.

Locally, Bishop Feehan and St. Mary-Sacred Heart in North Attleboro have students on a hybrid model. St. John the Evangelist School in Attleboro and St. Mary’s Catholic School in Mansfield reopened fully in-person to students in August.

Daniel Roy, superintendent of schools for the Diocese of Fall River, said all of the diocese’s 20 schools are following the same coronavirus protocols as public schools — distance, masks, enhanced cleaning and hand washing — and that the successful in-person start has come from a commitment to Catholic school education and the community’s buy-in.

It’s true those schools have had few positive cases. St. Mary-Sacred Heart and St. Mary’s Catholic School have had none. St. John the Evangelist School has seen fewer than 10, a representative from the Catholic School Alliance said.

But leadership from the schools said they are acutely aware that their luck could turn at any moment, and differences between the nature of public and private education affects their success.

Local public school officials say Baker’s push for full-time, in-person education is not feasible under the current health and safety guidance provided by the state.

Although their number of cases are higher, they agree that schools don’t seem to be a super-spreader like once feared. None of their cases were found to have originated, or transmitted, in school. And they want all of their students back in person — but not until it is safe.

To do so now would defy months-long state and federal guidance on proper spacing to prevent transmission of the coronavirus and decimate already-strained staffing and funding.

In all, local officials from private and public schools alike said pandemic education is an individual puzzle each school and district must solve themselves.

A key point of evidence? Even within the same municipality, the pandemic experience of schools are varied.

In Attleboro, Brennan Middle School shifted to remote-only education this week after several teachers tested positive for coronavirus or were determined to be a close contact of someone who had.

The majority of students returned to hybrid learning Thursday after three days remote, but four classrooms are continuing remotely as the school investigates a cluster of cases.

Superintendent David Sawyer said the temporary switch was ignited by a staff shortage due to the quarantines.

So when Baker talks about all schools returning fully in-person in January, Sawyer can’t see how that could happen in Attleboro.

“I certainly agree the goal is getting kids back in school,” Sawyer said. “I don’t object to the core goal there. But while some communities are virus free, Attleboro is metaphorically on fire. To act like we should be treating both communities in the same way — I can’t believe that’s the governor’s message for all of us. It’s hard to conceive that happening.”

Since opening in September, Attleboro Public Schools have seen a total of 72 positive cases, split between 59 students and 13 staff. Those positives triggered 571 quarantines.

And that data is two weeks old, from the last time the school reported its numbers on Nov. 20. On Wednesday, Sawyer said there were another 12 positive cases and about 100 more quarantines since.

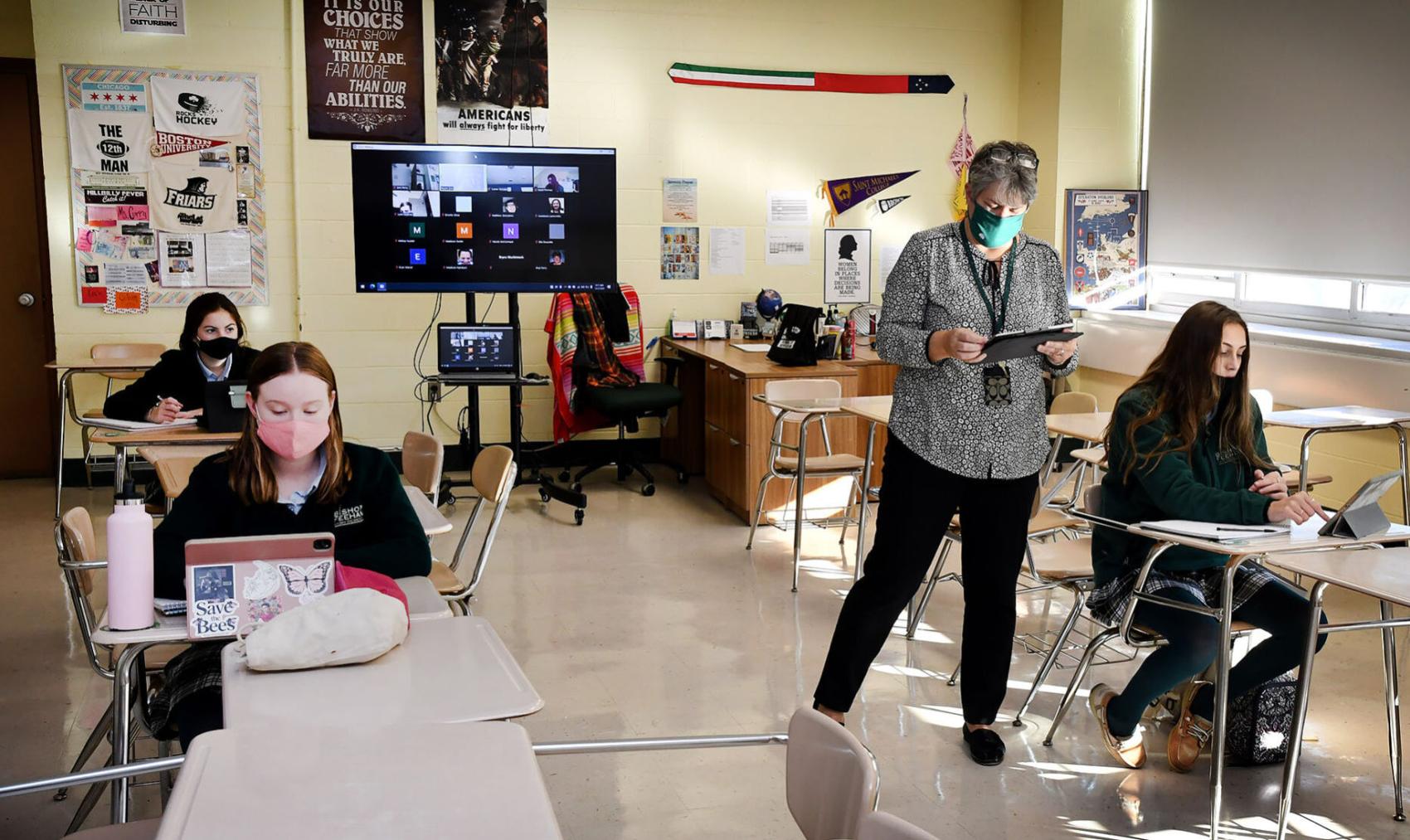

Bishop Feehan High School teacher Ann Perry conducts a freshman algebra class for both in-person and at-home students via Zoom.

Last week, Attleboro as a whole recorded 148 new cases, the biggest weekly total since the pandemic began in March. The city is in the highest category “red zone” of a state designation that measures prevalence of the virus.

But just on the other side of town, Bishop Feehan has remained largely virus-free.

“I think every building, every school is different,” Sullivan said. “In September, when Attleboro went red, we had zero cases. But I’m sure it could be the opposite, too. We could be in a position where Bishop Feehan is red, and the community is fine.”

One day at a time

Sullivan said he takes pandemic education one day at a time.

The school is cognizant of cases, both within the city and the school, and is ready to pivot to remote learning when necessary.

“To me, it feels like — we have four or five months before the vaccine is ready,” he said. “Can we stay healthy for that long? We’ve done it for three months. But can we keep it up? As long as we can keep our community healthy, we can keep our kids in school.”

Bishop Feehan remained hybrid when other schools in the diocese went back in-person because of space constraints.

Their building doesn’t allow for 1,100 students in grades 9-12 spaced 6 feet apart. So instead of 18 students in a classroom, hybrid learning brings about eight or nine in at a time.

But those at home half the week still have live access to their classes, thanks to a $100,000 investment into speakers, ceiling cameras and flat screens in each of the school’s classrooms.

Bishop Feehan High School freshman Maddie Mullen works on an algebra assignment while at-home students take part in the class via Zoom.

Students at home show up, in uniform, and can expect to be called on, Sullivan said.

“The word hybrid isn’t really defined,” he said. “What it means in every school is different.”

That effort feeds into the Catholic school’s philosophy. It ensures learning can happen at a near-regular pace with new curriculum daily — something he isn’t sure happens across the nation after nine months of disrupted education.

More important to that philosophy is raising people and not just scholars.

“There’s a lot more to being a healthy teenager than learning algebra,” Sullivan said. “Relationships, having something to engage the really busy brain of a teenager, adult mentors — these are all things you get at school. As school administrators everywhere, I think we’re worried about our kids and faculty’s health, but we’re extremely worried about our kids’ overall well-being.”

Sullivan said he believes school is the safest place for students during the pandemic. It’s six hours a day where students are wearing masks, distanced from one another and taking precautions under the eye of adults.

In the alternative, he doesn’t know what they are doing at the mall, or out with friends, or at work.

And he admits even when students leave school, he doesn’t know what they are doing — and that brings risk.

But for him, facing that uncertainty has meant building trust — especially as cases rise across the state and nation.

“All throughout this, we had to ask the community to really be communal,” he said.

Sullivan attributes that to some of their success, alongside the technology that has allowed students who aren’t feeling well to stay home and engage in their classes instead of taking a chance and potentially bringing the virus into the school.

On some days as many as 70 students have stayed home.

But Sullivan also recognizes that public school districts are faced with different constraints.

Bishop Feehan is a 9-12 only school in one building, while Attleboro Public Schools have nearly 6,000 students in grades K-12 across several buildings. Public schools have the added task of transportation, and often times higher class ratios.

“Every school is so different with its own strengths and weaknesses,” Sullivan said. “It was a very complicated puzzle for us to solve, and it’s more complicated for a full district to solve.”

In Attleboro, Sawyer said the biggest constraints come down to spacing, transportation and staffing.

Under the current state guidelines, students must sit 3 to 6 feet apart.

Sawyer said now, even with only half of the students in school at once, some classrooms are only able to keep desks 4 feet apart.

Bus fleets have accommodated a smaller number of students, but the same spacing wouldn’t be feasible with the entire school population.

And staffing levels are at risk, shown recently at the middle school.

Sawyer said beyond those mandatory quarantines, as cold and flu season kicks in, many staff are taking extra precautions when they have any symptoms.

“Under normal conditions, a lot of people would still come in and just take Dayquil and try to get through the day,” Sawyer said. “Now, we want people to stay home. Some of them might want to get a test. That puts additional pressures on our population. The substitute pool has dried up so we’re having a hard time staffing when that happens.”

When touring Carlisle Public School, a K-8 school, after making his push for in-person learning, Baker praised the school for utilizing every inch of space creatively.

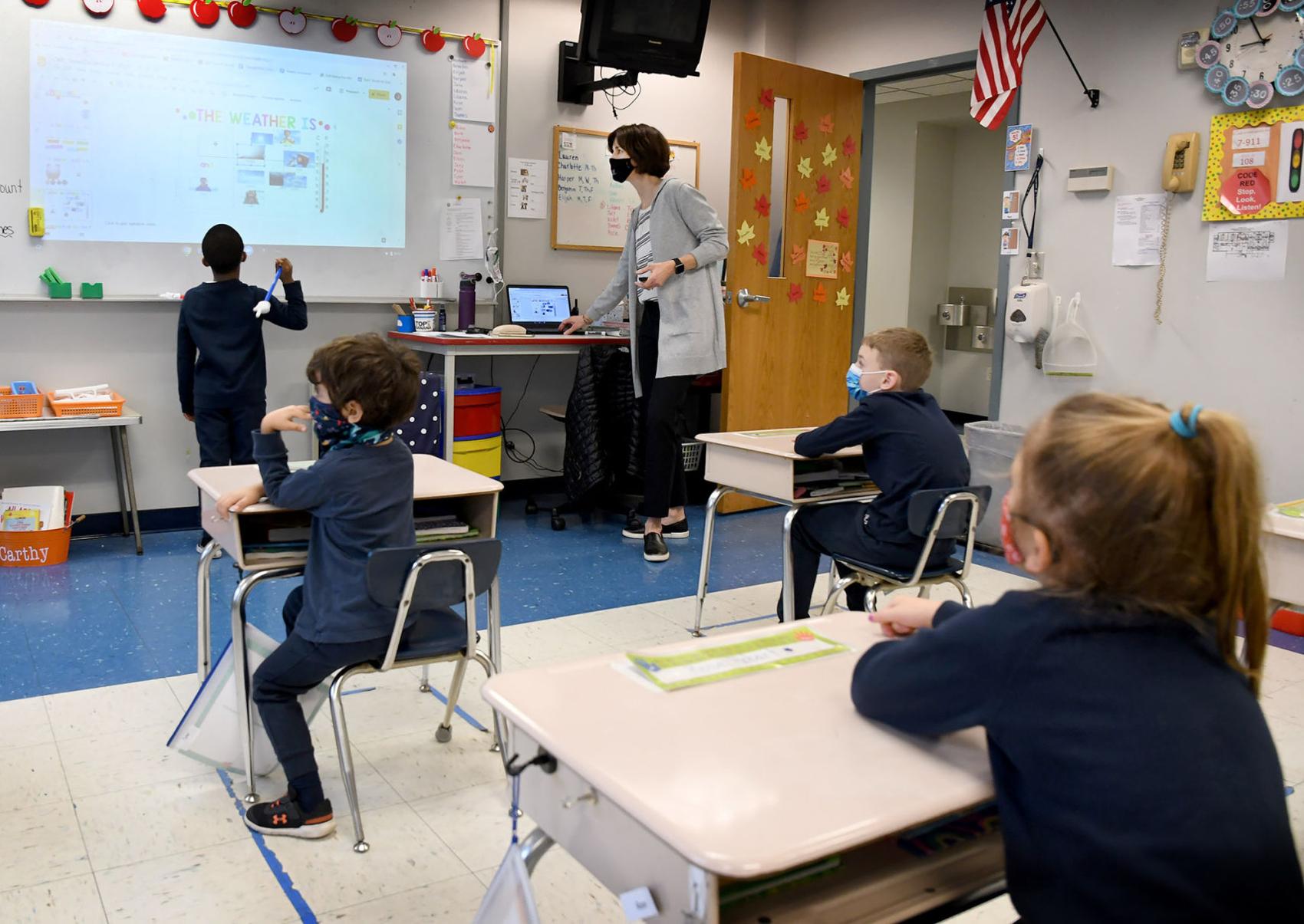

Elijah Gilot, a first grade student at St. Mary’s Catholic School in Mansfield, uses a wand with a Smartboard to recite the day, date and weather as teacher Julie McCarthy looks on. McCarthy teaches in one classroom with desks spaced 3 feet apart and has a second room available to use for small groups, recess, snack and lunch time. The wand Gilot is using is sanitized after each use.

At St. Mary’s Catholic School in Mansfield, Principal Matthew Bourque said the school has transformed the parish center and gymnasium into classrooms to find more space for all of its students.

But Sawyer said that is not feasible in Attleboro.

The district is already underfunded and has fewer staff members than an average district of its size.

“Utilizing those spaces doesn’t help you that much if you can’t staff them,” he said. “Until the state gives us different guidance, not much can change.

“I think the majority of families want much more than we can do. And I think people know we want our kids back in school, but we also want people to be safe. We have hundreds of families fully remote right now. If we go fully in-person, we’re not getting them back and we will lose more people.

“It’s not just what we think. It’s what our families think — and their opinions are complex and varied. It’s what the people doing the work think. Their opinions matter, too. It’s a complicated, no-win situation.”

On his end, Joe Amaral, who leads teachers in the Attleboro Education Association, said a move to in-person learning would be premature.

He believes the data the state is using is a mistake: It’s coming from the fall, when fewer students were in school and nice weather allowed fresh air to circulate through open windows.

“Those variables will be very different in the winter,” the union president said. “Everything we’ve done to maintain relative safety under the hybrid model so far will be diminished.”

Amaral said decisions around in-person learning should be left to local officials.

At St. Mary’s, Bourque said all of his hesitation around pandemic education was overshadowed by joy, as it is every year, when students walked in the building on the first day.

The decision to proceed fully in-person was “never a question,” Bourque said.

“We see teaching as a vocation and a service,” he said. “This is an opportunity to serve children in their needs.”

St. Mary’s is made up of 200 students from preschool to eighth grade. Students are spaced 6 feet apart in fifth grade up through the middle school, with 3-foot distancing in other grades, Bourque said.

And since it opened in late August, they haven’t had a single case.

“We weren’t sure in August or September if we would be like we are now,” Bourque said. “We had plans for possible quarantines. We had all of the protocols for things on Day One. The plans are all still there. We’re just glad we have not had to use them yet.”

He said the importance of full-time, in-person learning boiled down to community. The school’s stakeholders felt splitting the students up into different cohorts would be socially and emotionally devastating, especially for teenagers who rely on those relationships.

“Our students grow up together here and become a family of their own,” he said. “It wouldn’t be the same without all of them here at the same time.”

First grade teacher Julie McCarthy said teaching is more productive face-to-face, especially for younger students who are unfamiliar with teachers and their routines.

Julie McCarthy, a first grade teacher at St. Mary’s Catholic School in Mansfield, explains a lesson to her class.

They can build the social skills students learn at that age — sharing, patience, communication — and form relationships with peers and teachers.

Still, even full-time, in-person education is not normal.

McCarthy, who has taught for 20 years, said this year was an adjustment.

She wasn’t used to desks in rows, facing front – or constantly teaching the entire class at once instead of working with small groups.

“I didn’t sleep the entire month of August,” she said. “I was petrified at how I was going to teach. In my view, I felt we were doing it backwards. But it was about going back to the basics. I thought about the most important things to teach kids, and built from there. The end result is the same, you’re just getting there in a different way.”

While students in her classroom are seated 3 feet apart, she has access to a second classroom to use for snack breaks, recess or small groups, where half of the students can go with an assistant teacher to make room for the necessary space.

And just as teachers have adapted, students have, too.

They know to clean their desks before lunch and intuitively reach for hand sanitizer anytime they enter or leave a new area.

“They don’t even think about it anymore,” McCarthy said.

But Bourque also pointed out some differences between public and private school that have carried into the pandemic.

In March, as schools across the Commonwealth shut down on a Friday, St. Mary’s started remote learning by Monday. Education was their only focus.

He remembers a conversation with Mansfield Public Schools, who were wondering how they were going to feed students in the pandemic. Public schools operate as a social service, Bourque said, while Catholic schools don’t have some of the same obligations.

“This is so localized, even within the same town,” he said about decisions around pandemic education.

In North Attleboro, both St. Mary-Sacred Heart, a private school, and the public schools are using the hybrid model.

St. Mary-Sacred Heart Principal Charlotte Lourenco said the decision to reopen hybrid for the school’s 221 students, pre-K to eighth grade, came both from conversations with parents and considering the school’s 100-year-old facility.

“We have a plan to bring everyone back, but that doesn’t necessarily fall into what parents are asking for,” she said. “Many of our parents are committed to the 6 feet distance to ensure a safe environment for our students and faculty.”

Where space is available to maintain that — namely for the school’s youngest students from pre-K to second grade — students attend in-person full-time.

The school is also case-free, but Lourenco said it’s less a credit to the school than it is to the community.

“I’m under no illusion that, just like every other school, that’s a very fluid number,” she said. “What we have put in place has worked so far, but I’m not sure if it will continue. I don’t think we’re doing anything better than anyone else. Just like everyone we put in our social distancing, masks and touchless faucets and ordered our PPE in June. It’s not a success of the school, it’s a success of the school community and the parish. We all said yes.”

And any changes come from feedback from that community.

One example is the addition of live streams when students are home during the hybrid rotation.

That was added in after a survey of parents found that the live stream was more manageable for older kids than younger ones.

After they took a month to adjust to the new school environment, the school built in at least one live streamed content area for each grade, with older grades having up to four live classes a day.

And just like that decision, Lourenco said a return to full-time in-person will only come when the school community is ready.

“We’re making decisions based on the information and resources we have,” she said. “We’re just grateful there’s a spot for Catholic education in a year that’s so challenging.”

At North Attleboro Public Schools, Superintendent Scott Holcomb agreed that a full-time, in-person return is not currently feasible.

“I do agree with the philosophy of Gov. Baker that students are better off in school,” he said. “But it just doesn’t match up with the regulations.”

Holcomb said even to get every student to school under the current distancing guidelines, the district would have to double its bus fleets — without any extra funding to do so.

Then comes the concern of spacing of students, especially when taking mask breaks or eating where they are required to be 6 feet apart.

“I don’t think it’s feasible for North Attleboro or many districts across the Commonwealth for it to occur,” he said. “And to work all of those details out by January would be incredibly complicated, especially when you couple it with the increasing spike of Covid cases we’re seeing.”

His district has had a total of 22 positive cases this year.

Holcomb said the upcoming holidays are concerning because of the spike in cases expected to follow, and will be a test of quarantine regulations and how much school districts can take.

“It’s extremely challenging to do this,” he said.

For Roy, the superintendent of the Diocese of Fall River who oversees schools from the Attleboro area to the South Coast and Cape Cod – many of whom are approaching pandemic education in-person – the decision and the commitment to do so starts with the community.

“I think it has to begin as a community endeavor,” he said. “All of the stakeholders need to be on the same page. We all need to have a clearer understanding as to what the ‘why’ is. We are working toward providing a safe and meaningful education.

“With the situation put in that light — we’re all working for what’s best for our kids. There are some things you can’t control. Nobody has been able to tame this pandemic. But masks and hand washing and distance work. If we’re all doing that, I think we can get back to in-person learning effectively.”